3. Random variables and their distributions#

3.1. Random variables#

When performing an experiment, we are often more interested in specific properties of the outcomes rather than the outcomes themselves. For example, if we toss a coin three times, instead of focusing on each individual result (e.g., heads or tails for each toss), we may be more interested in the total number of head we observed.

This is where random variables come into play. A random variable, denoted as \( X \), is a variable that takes on different values based on the outcome of a random experiment. More formally, given an experiment with a sample space \( S \), a random variable is a function that maps each outcome \(s \in S \) to a real number in \( \mathbb{R} \). The value assigned to each outcome, \( X(s) \), depends on the random result of the experiment, represented by a probability function \( \mathbb{P} \).

To make this concrete, let’s return to the example of tossing a coin three times. The sample space \( S \) for this experiment consists of all possible sequences of heads (H) and tails (T):

Now, define the random variable \( X \) as the number of heads observed in the sequence. For each outcome in the sample space, the random variable assigns a corresponding value:

\( X(HHH) = 3 \) (three heads)

\( X(HHT) = X(HTH) = X(THH) = 2 \) (two heads)

\( X(HTT) = X(THT) = X(TTH) = 1 \) (one head)

\( X(TTT) = 0 \) (no heads)

In this way, the random variable simplifies the experiment’s outcomes, focusing on the specific feature we care about—in this case, the number of heads—while preserving the underlying randomness of the experiment.

We’ll now provide the formal definition of a discrete random variable. (We will discuss continuous random variables later in the quarter.)

Discrete random variable

A discrete random variable (RV) is a type of random variable that can take on either a finite or an infinite list of distinct values, such as \( x_1, x_2, x_3, \dots \). For a discrete random variable, the sum of the probabilities that \( X \) takes each of these values must equal 1. In other words:

The expression \( \mathbb{P}[X = x] \) is shorthand for the probability that the random variable \( X \) takes the value \( x \), which refers to the probability of the event \(\{s \in S \text{ such that } X(s) = x\}\) where the outcome of the experiment \( s \in S \) results in \( X(s) = x \).

3.2. Distributions and probability mass functions#

The probability mass function (PMF) of a discrete random variable is a function that assigns probabilities to each possible value of the random variable. The PMF is denoted by \( p_X(x) = \mathbb{P}[X = x] \), which gives the probability that \( X \) takes the value \( x \).

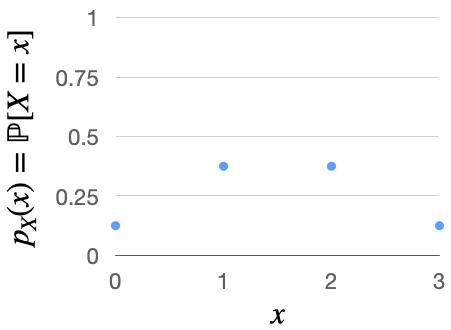

Example: Tossing coins.

Suppose we toss a coin three times, and let \( X \) represent the number of heads. The possible values of \( X \) are 0, 1, 2, and 3, and the PMF would look as follows:

\( p_X(0) = \mathbb{P}[X = 0] = \mathbb{P}[\{TTT\}] = \frac{1}{8} \)

\( p_X(1) = \mathbb{P}[X = 1] = \mathbb{P}[\{HTT, THT, TTH\}] = \frac{3}{8} \)

\( p_X(2) = \mathbb{P}[X = 2] = \frac{3}{8} \)

\( p_X(3) = \mathbb{P}[X = 3] = \mathbb{P}[\{HHH\}] = \frac{1}{8} \)

See Figure 3.1 for an illustration.

Fig. 3.1 PMF of the number of times a coin lands heads when tossed three times.#

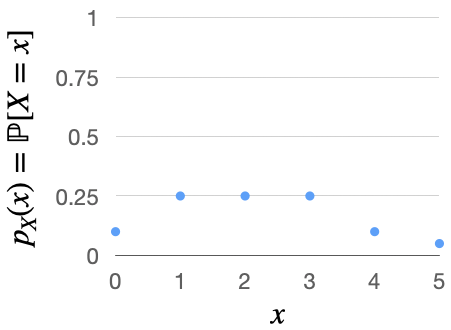

Example: Touchdown passes.

As another example, if our experiment is a game between the Bears and Packers, \(X\) might be the number of touchdown passes thrown by the Packers quarterback. Its PMF may look something like Table 3.1, as illustrated in Fig. 3.2.

\(x\) |

\( p_X(x) = \mathbb{P}[X = x] \) |

|---|---|

0 |

0.10 |

1 |

0.25 |

2 |

0.25 |

3 |

0.25 |

4 |

0.10 |

5 |

0.05 |

Fig. 3.2 Illustration of the PMF of the number of touchdown passes thrown by the Packers quarterback.#

3.3. Bernoulli and Binomial#

In the next few sections, we will cover famous families of discrete RVs. We begin with the definition of the simplest discrete RV.

Bernoulli distribution

We say that a RV \(X\) follows a Bernoulli distribution with parameter \( p \) if the probability that \( X = 1 \) is \( p \), and the probability that \( X = 0 \) is \( 1 - p \). This is typically written as \( X \sim \text{Bern}(p) \). For example, in an experiment that either succeeds or fails, \(X = 1\) would represent success, and \(X = 0\) would represent failure. This type of experiment is called a Bernoulli trial.

The Binomial distribution builds on the Bernoulli distribution.

Binomial distribution

Suppose we perform \( n \) independent Bernoulli trials with parameter \( p \). Let \( X \) represent the number of successes in these trials. In this case, we say that \( X \) follows a Binomial distribution with parameters \( (n, p) \), which is written as \( X \sim \text{Bin}(n, p) \).

Said another way, \( X \) is the sum of the outcomes of the \( n \) trials, expressed as \( X = X_1 + X_2 + \cdots + X_n \), where \( X_j = 1 \) if the \( j^{th} \) trial is a success, and \( X_j = 0 \) otherwise. Each of the individual random variables \( X_1, X_2, \dots, X_n \) is independent and identically distributed (which we often shorten to the acronym i.i.d.), following the Bernoulli distribution, i.e., \( X_j \sim \text{Bern}(p) \).

Example: Medical studies

Suppose that a patient has a probability of \( \frac{1}{10} \) of developing side effects from a particular medication. If the medication is tested on 1,000 patients, the number of patients who experience side effects can be represented by the random variable \( X \), which follows a Binomial distribution with parameters \( 1000 \) and \( \frac{1}{10} \). This is written as \( X \sim \text{Bin}\left(1000, \frac{1}{10}\right) \).

Example: Tennis tournaments

Suppose the probability that the winner of Wimbledon also wins the US Open in the same year is \( \frac{1}{4} \). Over the next 3 years, let \( X \) represent the number of years in which the Wimbledon winner also wins the US Open. In this case, \( X \) follows a Binomial distribution with parameters \( 3 \) and \( \frac{1}{4} \), written as \( X \sim \text{Bin}\left(3, \frac{1}{4}\right) \).

We will now work slowly through the Binomial distribution’s PMF, starting with the concrete example of the \(\text{Bin}\left(3, \frac{1}{4}\right)\) distribution.

Question: If \(X \sim \text{Bin}\left(3, \frac{1}{4}\right)\), what is the PMF of \(X\)?

We will work through the answer to this question step-by-step.

Step 1: Define the random variables. By definition, we know that \(X = X_1 + X_2 + X_3\), where \(X_1, X_2, X_3 \sim \text{Bern}\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)\). In other words, for each \(j = 1, 2, 3\), \(X_j = 1\) with probability \(\frac{1}{4}\) and \(X_j = 0\) with probability \(\frac{3}{4}.\)

Step 2: Define the goal. We aim to compute \(p_X(0)\), \(p_X(1)\), \(p_X(2)\), and \(p_X(3)\), where \(p_X(j) = \mathbb{P}[X = j]\).

Step 3: Compute the individual probabilities. We know that

Since \(X_1, X_2\), and \(X_3\) are all independent, we can write this as

Next,

Again, by independence,

Similarly,

Combining this with (3.2), we have that

Similarly,

and

Using the fact that \({n \choose 0} = 1\), we can rewrite (3.1), (3.3), (3.4), and (3.5) equivalently as

In other words,

Expanding this to the Binomial distribution more generally, we can deduce that if \(X \sim \text{Bin}\left(n, p\right)\), then

for \(0 \leq k \leq n.\) To see why, we know that \(X = X_1 + \cdots + X_n\), where each \(X_j \sim \text{Bern}(p)\). To calculate \(\mathbb{P}[X = k] = \mathbb{P}[X_1 + \cdots + X_n = k],\) there are \({n \choose k}\) ways to choose \(k\) of the \(n\) terms \(X_1, \dots, X_n\) to set equal to 1, with the rest equal to 0. For a particular choice, the probability that those \(k\) terms are equal to 1 and the remaining \(n-k\) terms are equal to 0 is \(p^k(1-p)^{n-k}\). Hence, (3.6) holds.

Example: Baseball World Series

This is Question 18 from Chapter 3 of [BH19].

The Boston Red Sox (RS) and the New York Yankees are facing off in the Baseball World Series. The first team to win four games takes home the championship. Suppose the probability that the Red Sox win any individual game is \( p = 0.6 \), and we assume that each game outcome is independent of the others.

Question: What is the probability the Red Sox win the world series?

Step 1: Define the goal. We want to compute the probability that the Red Sox win the series. This can happen if they win in 4, 5, 6, or 7 games. We express this mathematically as:

Step 2: Compute the individual probabilities. To find these probabilities, we begin by considering each possible outcome. First, \(\mathbb{P}[\text{RS win in 4 games}] = p^4\), since they must win the first four games.

Next, to win in 5 games rather than 4 games, the Red Sox must win exactly 3 out of the first 4 games, and then win the fifth game. A common mistake is to compute this as \( {5 \choose 4} p^4 (1-p) \), but this overlooks the fact that the Red Sox must win exactly 3 of the first 4 games. Instead, we calculate this using the Law of Total Probability (LTOP):

First, \(\mathbb{P}[\text{RS win in 5}\mid \text{RS win 3 out of first 4}] = p\). Next, \(\mathbb{P}[\text{RS win 3 out of first 4}] = {4 \choose 3} p^3 (1-p)\) by the same logic we used when we derived the PMF of the Binomial distribution: there are \({4 \choose 3}\) ways to choose which 3 of the 4 first games the Red Sox win. For a particular choice, the probability that they win those three but lose the other is \(p^3 (1-p)\). Finally, \(\mathbb{P}[\text{RS win in 5}\mid \text{RS don’t win 3 out of first 4}] = 0\). Therefore,

Finally, using the same logic as above, we leave it as an exercise to show that

and

Step 3: Compute the final answer. Now, we sum all these probabilities to get the overall probability that the Red Sox win the series:

Substituting \( p = 0.6 \) into this expression gives an approximate probability of 0.71, meaning the Red Sox have a 71% chance of winning the series.

3.4. Hypergeometric#

We have a bag containing \( w \) white marbles and \( b \) black marbles. Suppose we draw \(n\) marbles out of the bag with replacement, and let \(X\) be the number of white marbles. Then \(X \sim \text{Bin}\left(n, \frac{w}{w+b}\right)\) because each marble we draw is white with probability \(\frac{w}{w+b}\). However, if we draw \(n\) marbles out of the bag without replacement, the number of white marbles follows the Hypergeometric distribution.

Hypergeometric distribution

Suppose we have a bag containing \( w \) white marbles and \( b \) black marbles. We draw \( n \) marbles from this bag at random without replacement. All \({w + b \choose n}\) choices of the \(n\) marbles are equally likely.

Let \( X \) be the number of white marbles among the \(n\) drawn from the bag. We say that the random variable \( X \) follows a Hypergeometric distribution with parameters \( w \), \( b \), and \( n \), denoted as \( X \sim \text{HGeom}(w, b, n) \).

Since all combinations of \(n\) marbles are equally likely, the probability that \( X = k \), meaning exactly \( k \) white marbles are drawn, can be calculated as:

To find the number of favorable outcomes, we count the ways to choose \( k \) white marbles from the \( w \) available and \( n-k \) black marbles from the \( b \) available. This gives:

Example: Endangered species.

This is Example 3.4.3 from [BH19].

Suppose you’re a scientist in a jungle with \(N\) endangered tigers. You tag \(m\) tigers and release them into the wild. Then, you recapture \(n\) random tigers and see how many are tagged. If \(X\) is the number of tagged tigers in your random sample, then \(X \sim \text{HGeom}(m, N-m, n)\).

Example: Card hands.

This is Example 3.4.4 from [BH19].

Suppose you draw a 5-card hand from a shuffled deck. Let \(X\) be the number of aces in your hand. Then \(X \sim \text{HGeom}(4, 48, 5)\).

The following table summarizes the correspondance between the different colored marbles and the categories of objects in the previous two examples.

\(w\) white marbles |

\(b\) black marbles |

|---|---|

\(m\) tagged tigers |

\(N-m\) untagged tigers |

4 aces |

48 non-aces |

3.5. Discrete uniform#

The final example of a named distribution we will see in this chapter is the discrete uniform distribution.

Discrete uniform distribution

Let \( C = \{x_1, \dots, x_n\} \) be a finite set of numbers. From this set, we randomly select one number, \( X \), with each element equally likely. We say that \( X \) has the discrete uniform distribution, denoted by \( X \sim \text{Disc}(C) \). The PMF for \( X \) is

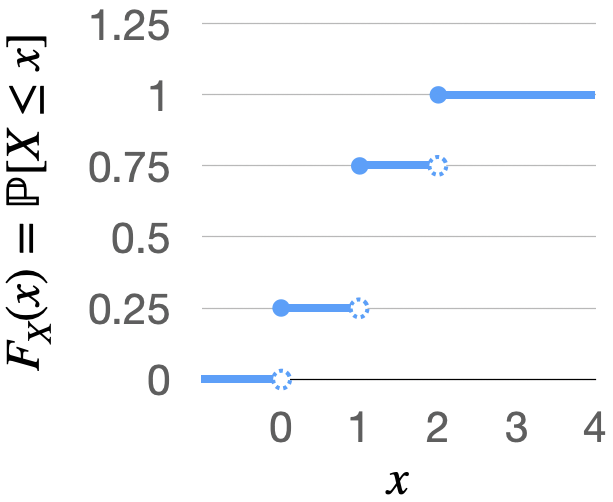

3.6. Cumulative distribution functions#

In addition to a RV’s PMF, we will see that it can be useful to work with the RV’s cumulative distribution function (CDF). The CDF of a RV \(X\) is defined as \( F_X(x) = \mathbb{P}[X \leq x] \), representing the probability that \( X \) takes a value less than or equal to \( x \).

Suppose we toss a coin twice. Let \( X \) be the number of heads. In this case, \( X \) follows a binomial distribution, \( X \sim \text{Bin}(2, \frac{1}{2}) \). The probability mass function of \( X \) is as follows:

\( p_X(0) = \mathbb{P}[\{TT\}] = \frac{1}{4} \),

\( p_X(1) = \mathbb{P}[\{HT, TH\}] = \frac{1}{2} \),

\( p_X(2) = \frac{1}{4} \).

We plot the CDF of \(X\) below.

Fig. 3.3 CDF of the number of times a coin lands heads when tossed two times.#

For example, we can see that:

\( F_X(-1) = \mathbb{P}[X \leq -1] = 0 \),

\( F_X(0) = \mathbb{P}[X \leq 0] = \mathbb{P}[X = 0] = \frac{1}{4} \),

\( F_X(1.5) = \mathbb{P}[X \leq 1.5] = \mathbb{P}[X = 0 \text{ or } X = 1] = \frac{3}{4} \), and

\( F_X(2) = \mathbb{P}[X \leq 2] = 1 \).

Additionally, the probability that \( X \) exceeds a certain value \( x \) is given by \( \mathbb{P}[X > x] = 1 - \mathbb{P}[X \leq x] = 1 - F_X(x) \).

3.7. Functions of random variables#

For a random variable \( X \) and a function \( g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} \), the transformed variable \( g(X) \) is also a random variable.

Example: PMF of \( Y = 2|X| \) for \( X \sim \text{Disc}(\{-1, 0, 1, 2, 3\}) \).

Suppose \( X \sim \text{Disc}(\{-1, 0, 1, 2, 3\}) \).

Question: What is the PMF of \( Y = 2|X| \)?

Step 1: Identify the PMF of \( X \). Since \( X \) is uniformly distributed over the set \( \{-1, 0, 1, 2, 3\} \), the probability of each value is:

Step 2: Compute the PMF of \( Y \).

\( p_Y(0) = \mathbb{P}[Y = 0] = \mathbb{P}[2|X| = 0] = \mathbb{P}[X = 0] = \frac{1}{5} \),

\( p_Y(1) = 0 \), since there is no value of \( X \) that satisfies \( 2|X| = 1 \),

\( p_Y(2) = \mathbb{P}[Y = 2] = \mathbb{P}[2|X| = 2] = \mathbb{P}[X = 1] + \mathbb{P}[X = -1] = \frac{2}{5} \),

\( p_Y(4) = \mathbb{P}[Y = 4] = \mathbb{P}[2|X| = 4] = \mathbb{P}[X = 2] = \frac{1}{5} \),

\( p_Y(6) = \mathbb{P}[Y = 6] = \mathbb{P}[2|X| = 6] = \mathbb{P}[X = 3] = \frac{1}{5} \).

Therefore, we have that

Example: Value of a stock price.

This is Example 3.7.2 from [BH19].

A stock price starts at $0, and each day the price either increases or decreases by $1 with equal probability. Let \( Y \) be the stock price on the 100th day.

Question: What is the PMF of \( Y \)?

Step 1: Determine if \( Y \) is related to any familiar discrete RV. Let \( X \) be the number of days (out of 100) that the stock price increases by $1. Since each day the price has a 50% chance of increasing, \( X \) follows a binomial distribution: \(X \sim \text{Bin}\left(100, \frac{1}{2}\right).\)

Step 2: Establish the relationship between \( X \) and \( Y \). If \( X = j \), then on \( j \) days the price increased by $1, and on \( 100 - j \) days it decreased by $1. Therefore, the price on the 100th day is: \(Y = j - (100 - j) = 2j - 100 = 2X - 100.\)

Step 3: Compute the PMF of \( Y \) using the PMF of \( X \). First, since \(X \in \{0, 1, 2, \dots, 100\}\) and \(Y = 2X - 100\), we know that \(Y\) must be an even number between \(-100\) and \(100\). For any other number \(k\), \(p_Y(k) = \mathbb{P}[Y = k] = 0\).

Next, suppose \(k\) is an even number between \(-100\) and \(100\). We want to find the probability that \( Y = k \), which corresponds to the probability that \( X = \frac{100 + k}{2} \). Thus, the PMF of \( Y \) is given by:

3.8. Independence of random variables#

Random variables \( X \) and \( Y \) are said to be independent if the joint probability that \( X \) is less than or equal to some value \( x \) and \( Y \) is less than or equal to some value \( y \) can be expressed as the product of their individual probabilities. Formally, \( X \) and \( Y \) are independent if: \(\mathbb{P}[X \leq x, Y \leq y] = \mathbb{P}[X \leq x] \mathbb{P}[Y \leq y]\) for all \(x, y \in \mathbb{R}.\)

In the case of discrete random variables, independence means that the joint probability of \( X = x \) and \( Y = y \) is the product of their individual probabilities. That is, \( X \) and \( Y \) are independent if: \(\mathbb{P}[X = x, Y = y] = \mathbb{P}[X = x] \mathbb{P}[Y = y].\)