4. Expectation#

4.1. Definition of expectation#

While the full distribution of a RV provides a complete description of its behavior, it can be cumbersome to work with since it involves many probabilities. Instead, it is often more practical to summarize a distribution with just a few key numbers that describe the “average” value of the RV and how much it varies or spreads.

One important summary is the expected value.

Expected value

For a RV \( X \) that takes distinct values \( x_1, x_2, \dots \), the expected value, denoted \( \mathbb{E}[X] \), is given by:

This formula gives a weighted average of the possible values of \( X \), where the weights are the probabilities associated with each value.

For example, let \( X \sim \text{Bern}(p) \) be a Bernoulli random variable that takes the value 1 with probability \( p \) and 0 with probability \( 1 - p \). The expected value of \( X \) is \(\mathbb{E}[X] = 0 \cdot \mathbb{P}[X = 0] + 1 \cdot \mathbb{P}[X = 1] = 1 \cdot p = p.\) This means that the expected value of a Bernoulli random variable is simply \( p \), the probability of success.

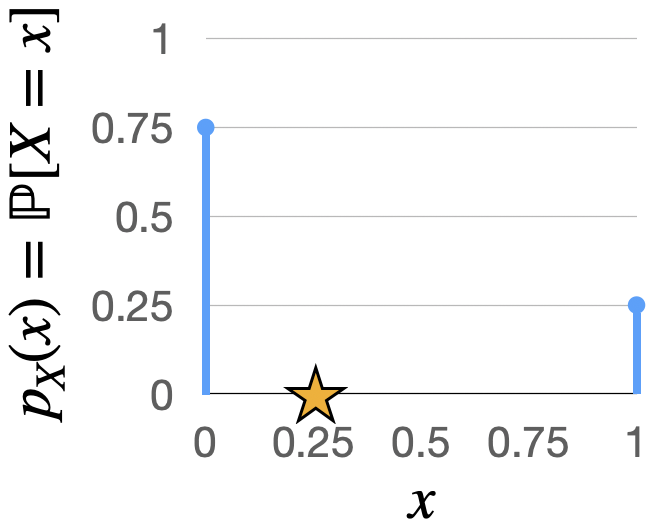

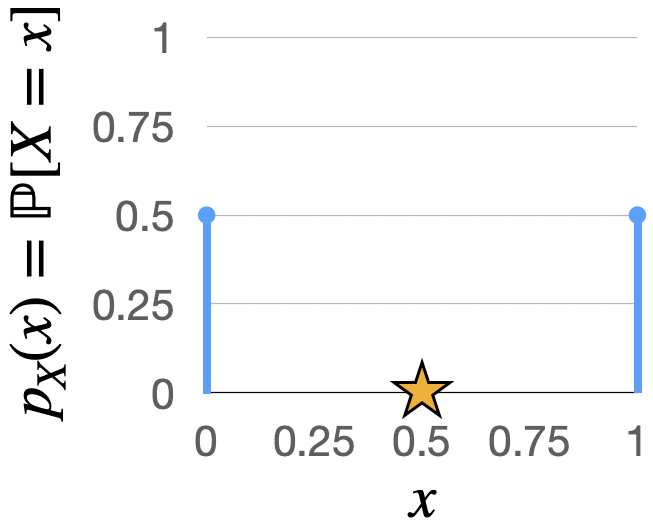

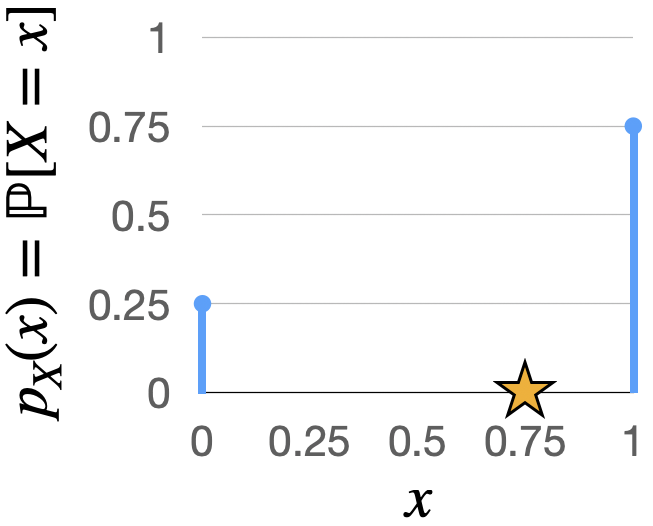

Below, we illustrate the \(\text{Bern}(p)\) PMF for several choices of \(p\), together with the expected value.

Fig. 4.1 PMF of the \(\text{Bern}(0.5)\) distribution, with the expected value marked by a star.#

Fig. 4.2 PMF of the \(\text{Bern}(0.5)\) distribution, with the expected value marked by a star.#

Fig. 4.3 PMF of the \(\text{Bern}(0.75)\) distribution, with the expected value marked by a star.#

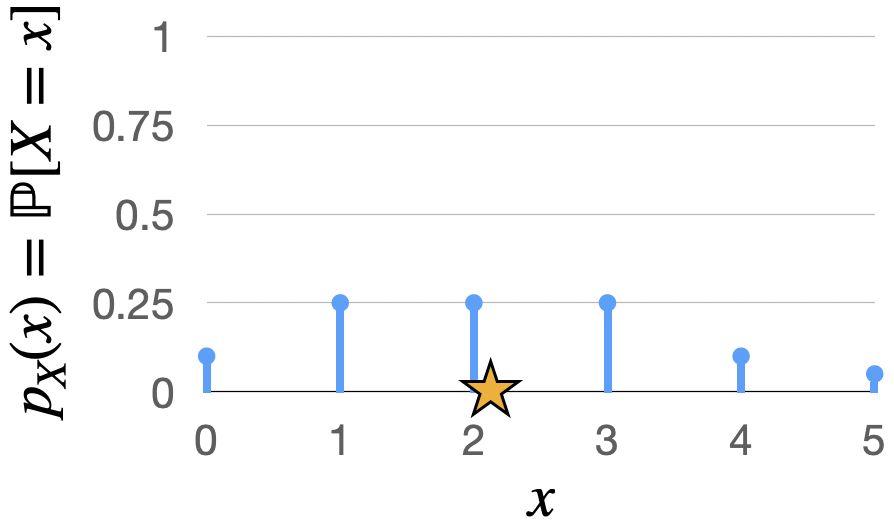

As another example, let \(X\) be the number of touchdown passes thrown by the Packers quarterback in a game between the Bears and the Packers, with its PMF as follows:

\(x\) |

\( p_X(x) = \mathbb{P}[X = x] \) |

|---|---|

0 |

0.10 |

1 |

0.25 |

2 |

0.25 |

3 |

0.25 |

4 |

0.10 |

5 |

0.05 |

Then \(\mathbb{E}[X] = 0 \cdot 0.1 + 1 \cdot 0.25 + 2 \cdot 0.25 + 3 \cdot 0.25 + 4 \cdot 0.1 + 5 \cdot 0.05 = 2.15\).

We illustrate the PMF and expected value of this random variable below.

Fig. 4.4 Illustration of the PMF and expected number of touchdown passes thrown by the Packers quarterback.#

Example: Investment returns.

Suppose an investment has a 50% chance of gaining 20% and a 50% chance of losing 10%. To calculate the expected return, we multiply the probability of each outcome by the corresponding return and sum the results, so the expected return is \(0.5 \cdot 0.2 + 0.5 \cdot (-0.1) = 0.05.\) In other words, the expected return of this investment is 5%.

Meanwhile, suppose the investment has a 50% chance of gaining 200% and a 50% chance of losing 190%. The expected return is \(0.5 \cdot 2.0 + 0.5 \cdot (-1.9) = 0.05.\) Even though the potential gains and losses are much larger in this case, the expected return is still 5% (however, the variance is different, a topic we will return to later in this chapter).

4.2. Linearity of Expectation#

One of the fundamental properties of expectation is linearity: the expected value of a sum of random variables equals the sum of their individual expected values, regardless of whether these random variables are independent.

Linearity of expectation

Sum of random variables: The expectation of the sum of two random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) can be expressed as: \(\mathbb{E}[X + Y] = \mathbb{E}[X] + \mathbb{E}[Y].\) Notably, this property holds even if \(X\) and \(Y\) are not independent.

Scaling of random variables: For a random variable \(X\) and any constant \(c \in \mathbb{R}\), the expectation scales linearly: \(\mathbb{E}[cX] = c \mathbb{E}[X].\)

These properties allow us to decompose complex random variables into simpler parts for easier computation.

For example, let \(X \sim \text{Bin}(n, p)\) be a binomial RV. We know that \(X = I_1 + I_2 + \cdots + I_n\), where each \(I_j \sim \text{Bern}(p)\). Since \(\mathbb{E}[I_j] = p\), we can conclude that \(\mathbb{E}[X] = \mathbb{E}[I_1 + I_2 + \cdots + I_n] = \mathbb{E}[I_1] + \cdots + \mathbb{E}[I_n] = np.\)

As another example, suppose we have a bag with \(w\) white marbles and \(b\) black marbles. Let \(X \sim \text{HGeom}(w, b, n)\) represent the number of white marbles when we draw \(n\) marbles out of the bag randomly without replacement. Define the RV \(I_j\) such that \(I_j = 1\) if the \(j\)-th marble in the sample is white, and \(I_j = 0\) otherwise. Then, the RV \(X\) can be expressed as \(X = I_1 + I_2 + \cdots + I_n.\) The RVs \(I_1, \dots, I_n\) are not independent, but linearity of expectation still applies. For each indicator variable \(I_j\),

To calculate this probability, let’s start with the first marble. Since there are \(w\) white marbles and \(w+ b\) total marbles, \(\mathbb{P}[1^{st} \text{ marble is white}] = \frac{w}{w+b}\). Next,

If we know the first marble is white, then there are \(w-1\) white marbles out of the remaining \(w+b-1\) marbles. Therefore, \(\mathbb{P}[2^{nd} \text{ marble is white} \mid 1^{st} \text{ marble is white}] = \frac{w-1}{w+b-1}\). Meanwhile, \(\mathbb{P}[2^{nd} \text{ marble is white} \mid 1^{st} \text{ marble is black}] = \frac{w}{w+b-1}\). Therefore,

Returning to (4.1), we have that \(\mathbb{E}[I_j] = \mathbb{P}[j^{th} \text{ marble is white}] = \frac{w}{w+b}\). In other words, each marble we draw is equally likely to be white when considered in isolation (though not when conditioned on the previous draws), a phenomenon known as symmetry. In the end, we have that \(\mathbb{E}[X] = \mathbb{E}[I_1 + \dots + I_n] = \mathbb{E}[I_1] + \cdots + \mathbb{E}[I_n] = \frac{nw}{w+b}\).

We note that the events that the \(1^{st}\) and \(2^{nd}\) marbles are white are not independent: \(\mathbb{P}[2^{nd} \text{ marble is white} \mid 1^{st} \text{ marble is white}] = \frac{w-1}{w+b-1} < \mathbb{P}[2^{nd} \text{ marble is white}] = \frac{w}{w+b}\). This intuitively makes sense: once you know the first marble is white, there are fewer white marbles to choose from.

4.3. Geometric and negative binomial#

Geometric distribution

The geometric distribution arises from a sequence of independent Bernoulli trials, where each trial results in a success with probability \( p \) and a failure with probability \( q = 1 - p \). In this context, let the random variable \( X \) represent the number of failures that occur before the first success. We say that \( X \) follows a geometric distribution with parameter \( p \), denoted as \( X \sim \text{Geom}(p) \).

The probability mass function \( p_X(k) \) of a geometric random variable is \(\mathbb{P}[X = k] = p_X(k) = q^k p\) for \(k = 0, 1, 2, \dots\). This expression reflects the probability of having \( k \) consecutive failures (each occurring with probability \( q \)) followed by a single success (occurring with probability \( p \)). For example, if we observe the sequence “FFFFFS,” where five failures are followed by one success, the probability of this specific sequence occurring is given by \( q^5 p \).

The expectation \( \mathbb{E}[X] \) for a geometric random variable can be derived by summing over all possible values of \( k \):

The following distribution is closely related to the geometric distribution.

First success distribution

Suppose we perform a sequence of independent Bernoulli trials, where each trial results in a success with probability \( p \) and a failure with probability \( q = 1 - p \). Let \( Y \) be the total number of trials required to achieve the first successful outcome, including the successful trial itself. Then \(Y\) follows the first success distribution with parameter \(p\), denoted \( Y \sim \text{FS}(p) \).

The key relationship between \( Y \) and the geometric distribution is that \( Y \) counts the total number of trials, while the geometric random variable \( X \) only counts the number of failures before the first success. Mathematically, \(Y = X+1\), where \( X \sim \text{Geom}(p) \). Since \( Y \) simply adds one successful trial to the count of failures, the expected value of \( Y \) can be derived using the linearity of expectation:

In other words, on average, the number of trials required to achieve the first success (including the successful trial itself) is \( \frac{1}{p} \).

Example

Imagine a couple who decides to continue having children until they have at least one boy and one girl. Each child is either a boy or a girl, and each outcome is independent with an equal probability of 50%. The couple never has twins, so each child is born individually.

Question: What is the expected number of children they’ll have?

For example, if the sequence of births is G-G-G-B, they would have four children in total. If the sequence is B-B-G, they would have three children in total.

Step 1: Define the Random Variables

Let \( X \) denote the number of children needed, starting from the second child, to get a gender different from the firstborn. Essentially, \( X \) is the number of additional children required after the first child to achieve a child of the opposite gender. For example, if the birth order is G-G-G-B, then \(X = 3\) and if the birth order is B-B-G, then \(X = 2\).

Step 2: Define the Goal

The goal is to compute the expected number of children the couple will have, which can be expressed as \(\mathbb{E}[\# \text{children}] = \mathbb{E}[1 + X] = 1 + \mathbb{E}[X]\). Here, the “1” represents the firstborn, and \( X \) represents the additional children needed.

Step 3: Identify the Distribution of \( X \)

Notice that \( X \) represents the number of children until the couple has a child of the opposite gender from the firstborn. This is equivalent to the distribution \( \text{FS}(\frac{1}{2}) \), which describes the number of trials until the first success, given a success probability of \( \frac{1}{2} \). The expected value of \( X \) is \(\mathbb{E}[X] = \frac{1}{\frac{1}{2}} = 2\).

Step 4: Calculate the Final Answer

The total expected number of children the couple will have is: \(\mathbb{E}[\# \text{children}] = 1 + \mathbb{E}[X] = 1 + 2 = 3.\)

Example

This is Example 4.3.12 from [BH19].

This is a classic problem called the coupon collector problem. Imagine that there are \( n \) different types of toys that you are trying to collect. Each time you acquire a toy, it is equally likely to be any one of the \( n \) types, regardless of the toys you have collected so far. The goal is to determine the expected number of toys you need to collect in order to have at least one of each type.

Question: What is the expected number of toys needed to complete the set?

Step 1: Define the Random Variables

Let \( N \) denote the total number of toys needed to collect all \( n \) different types. This can be expressed as the sum of individual random variables \( N_1, N_2, \ldots, N_n \), where:

\( N_1 \) is the number of toys needed to collect the first type that you haven’t seen before. Clearly, \( N_1 = 1 \) because the first toy you collect will always be a new type.

\( N_2 \) is the number of additional toys needed to collect a second type that you haven’t seen before.

\( N_j \) is the number of additional toys needed to collect the \( j \)-th type that you haven’t seen before.

Thus, \(N = N_1 + N_2 + \cdots + N_n.\)

Step 2: Identify the Distribution of \( N_j \)

Each \( N_j \) follows the first success distribution, where the probability of success depends on how many types are yet to be collected.

\( N_2 \sim \text{FS}\left(\frac{n-1}{n}\right) \), as you are looking for a toy of a new type among the \( n \) available types, given that you’ve already collected one type.

More generally, \( N_j \) follows \( \text{FS}\left(\frac{n-j+1}{n}\right) \) because you are searching for a new type of toy among the remaining \( n - (j - 1) \) types.

Step 3: Compute the Final Answer The expected total number of toys \( N \) is given by the sum of the expected values of each \( N_j \). Therefore,

\[\begin{equation*} \mathbb{E}[N] = \mathbb{E}[N_1] + \mathbb{E}[N_2] + \cdots + \mathbb{E}[N_n] = 1 + \frac{n}{n-1} + \frac{n}{n-2} + \cdots + n \approx n \log n. \end{equation*}\]

We will introduce one more distribution that is closely related to the geometric distribution.

Negative binomial distribution

Suppose we perform a sequence of independent Bernoulli trials, where each trial results in a success with probability \( p \). Let \(X\) be the number of failures before \(r^{th}\) success. Then we say that \(X\) follows the *negative binomial distribution with parameters \((r,p)\), denoted \(X \sim \text{NBin}(r,p)\).

To determine the PMF of \(X\), we will start with an example, where \(X \sim \text{NBin}(5, p)\), which is the number of failures before the fifth success. Under the following sequences (with 1 representing success and 0 representing failure), there are three failures before the fifth success: 11010011, or 11010101, or … Indeed, to represent three failures before the fifth success, the last digit in these sequences must be a 1, and must be preceded by three 0s (the three failures) and four 1s (the four other successes), arranged in any order. There are \({3 + 4 \choose 3}\) different sequences of this form: imagine drawing seven fill-in-the-blank slots, three of which we must fill in with 0s, and the rest with 1s. Each sequence has a probability of \(p^5(1-p)^3\) (for the five success and the three failures). Therefore

By the exact same logic, for \(X \sim \text{NBin}(r,p)\),

for \(n = 0, 1, 2, \dots\). To calculate the expectation of \(X\), we can write it as \(X = X_1 + \cdots + X_r\) where \(X_1\) is the number of failures until the \(1^{st}\) success, \(X_2\) is the number of failures between \(1^{st}\) and second \(2^{nd}\) successes, and so on. We can see that \(X_i \sim \text{Geom}(p)\), so by linearity of expectation, \(\mathbb{E}[X] = r \cdot \frac{1-p}{p}\).

Example

This season, suppose Arsenal wins each soccer game independently with a probability of 0.7.

1. Number of Games Before a Win. Let \( X \) be the number of games Arsenal plays before winning their first game. Since each game is independent and has a fixed probability of success (a win) of 0.7, \(X \sim \text{Geom}(0.7).\)

2. Number of Losses Before Winning Five Games. Next, let \( Y \) represent the number of games Arsenal loses before achieving five wins. Then \(Y \sim \text{NBin}(5, 0.7).\)

4.4. Indicator random variables and the fundamental bridge#

An indicator random variable is a simple variable that indicates whether a specific event has occurred or not.

Indicator random variable

Given an event \(A\), define the RV \( I_A \) is as follows:

The fundamental relationship between the probability and expectation of an indicator RV is captured by the following formula:

This equation shows that the expected value of an indicator random variable \( I_A \) is equal to the probability of the event \( A \).

Example

Suppose a university is deciding whether to test all 100 people in a dormitory for COVID-19. Before conducting individual tests, they will test the sewage. If the sewage sample tests positive, they will test all 100 people in the dorm. Let’s model this situation using indicator random variables:

Each person in the dorm is independently negative with a probability of 0.9.

Let \( X \) represent the total number of tests conducted, including the sewage test.

Let \( A \) denote the event that the sewage test is positive, with indicator RV \(I_A\).

The total number of tests \( X \) is \(X = 1 + 100 \cdot I_A\). Here, the “1” represents the initial sewage test, and the term \( 100 \cdot I_A \) represents the additional 100 individual tests if the sewage test is positive. To find the expected number of tests \( \mathbb{E}[X] \), we first need to determine \( \mathbb{E}[I_A] \). The probability of \( A \), which is the probability that at least one person in the dorm has COVID-19, is given by \(\mathbb{P}[A] = 1 - \mathbb{P}[\text{no one has COVID}] = 1 - 0.9^{100}.\) Therefore, the expected value of \( I_A \) is \(\mathbb{E}[I_A] = \mathbb{P}[A] = 1 - 0.9^{100}\).

Now, we can calculate the expected number of tests:

Example

This is Example 4.4.5 from [BH19].

In a room with \( n \) people, each person’s birthday is equally likely to fall on any of the 365 days of the year. The goal is to calculate the expected number of birthday matches, denoted as \( Y \), where a birthday match occurs if two people share the same birthday.

Step 1: Define the random variables. We begin by labeling the people in the room as \(1, 2, 3, \dots, n \) and ordering the \( \binom{n}{2} \) pairs of people. Let \( Y \) represent the total number of birthday matches, which can be written as the sum of indicator variables \( I_j \), where \( I_j = 1 \) if the \( j \)-th pair of individuals share a birthday, and \( I_j = 0 \) otherwise. Thus, we can express \( Y \) as:

Step 2: Define the goal. We aim to compute \( \mathbb{E}[Y] \), the expected number of birthday matches. Using the linearity of expectation, we can break this sum down into the individual expectations for each pair:

Step 3: Calculate the probability for each pair. For any pair of people, the probability that they share the same birthday can be computed as follows. The probability that the first person in the pair is born on any specific day (e.g., January 1st) is \( \frac{1}{365} \), and the probability that the second person is also born on that same day is also \( \frac{1}{365} \). Therefore, the probability that both individuals in a pair are born on the same day is:

Step 4: Compute the final answer. Using this probability, we can now compute the expected number of birthday matches. Since there are \( \binom{n}{2} \) pairs in the room, the expected number of matches is:

For example, in a room with 70 people, the expected number of birthday matches is:

4.5. Law of the unconscious statistician#

The law of the unconscious statistician (LOTUS) is a simple formula for calculating the expected value of functions of RVs, namely \(\mathbb{E}[g(X)]\) where \(X\) is a RV and \(g\) is any function.

Law of the unconcious statistician

For any function \(g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\), \(\mathbb{E}[g(X)] = \sum_x g(x)\mathbb{P}[X = x]\).

Example: St. Petersburg paradox

This is Example 4.3.14 from [BH19].

Suppose you play a game where you flip a fair coin repeatedly until it lands heads. The payout structure is as follows: if the 1st heads appears on the 1st round, you win $2; if it appears on the 2nd round, you win $4; if it appears on the \(i\)-th round, you win \(2^i\) dollars.

Question: Let \( X \) represent your total winnings from the game. What is the expected value \( \mathbb{E}[X] \)?

Step 1: Define the random variables. Let \( N \) denote the number of rounds it takes to get the first heads. Since the winnings are determined by the round on which the first heads occurs, we can express \( X \) as a function of \( N \): \(X = 2^N = g(N).\)

Step 2: Define the goal. We want to calculate the expected value of \( X \). Using the fact that \( X = g(N) \), we compute \( \mathbb{E}[X] \) as:

Step 3: Is \(N\) a familiar RV? The random variable \( N \) follows the first success distribution because it counts the number of rounds until the first heads appears in a sequence of fair coin flips, including that first head. Specifically, \( N \sim \text{FS}(\frac{1}{2}) \), which means the probability that the first heads occurs on the \(n\)-th round is:

Step 4: Compute the expected value. Substituting the expression for \( g(n) = 2^n \) and the probability \( \mathbb{P}[N = n] = \frac{1}{2^n} \) into the expected value formula, we get:

Each term simplifies to 1, and since there are infinitely many terms, the sum diverges: \(\mathbb{E}[X] = \infty.\) Thus, the expected winnings in the St. Petersburg game are infinite.

This result is counterintuitive because it suggests that a rational person should be willing to pay any amount to play this game, despite the unrealistic nature of achieving such high winnings. In fact, since \(N \sim \text{FS}\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\), so the expected number of rounds of the game is \(\mathbb{E}[N] = 2\).

It’s important to note that \( \infty = \mathbb{E}[X] = \mathbb{E}\left[2^N\right] \not= 2^{\mathbb{E}[N]} = 4\).

To make the game more realistic, suppose you impose a bound of 40 rounds. In this case, the maximum potential winnings are $\( 2^{40} \), which is approximately one trillion dollars. However, the expected value of \( X \) when limiting the number of rounds to 40 can be calculated as \(\mathbb{E}[X] = \sum_{n = 1}^{40} \frac{1}{2^n} \cdot 2^n = 40.\) By capping the game at 40 rounds, the expected winnings become finite and are equal to 40 dollars.

4.6. Variance#

Variance is a measure that describes how “spread out” a probability distribution is. It quantifies the average squared deviation of a random variable \( X \) from its mean.

Variance

The variance of a RV \(X\) is defined as \(\text{Var}(X) = \mathbb{E}\left[(X - \mathbb{E}[X])^2\right].\)

4.6.1. Why variance is defined this way#

A natural first attempt to measure spread might be to compute the expectation of the difference between the random variable and its mean, i.e., \( \mathbb{E}[X - \mathbb{E}[X]] \). However, this turns out to be zero by linearity of expectation: \(\mathbb{E}[X - \mathbb{E}[X]] = 0.\) Next, one might try using the absolute deviation, \( \mathbb{E}[|X - \mathbb{E}[X]|] \), but this function is not differentiable, which makes it more difficult to work with mathematically. The definition of variance as \(\mathbb{E}\left[(X - \mathbb{E}[X])^2\right]\) both captures the spread of a distribution and is easy to work with mathematically.

4.6.2. Standard deviation#

It’s important to note that when a RV is measured in terms of some unit (say, inches), then its variance will be measured in terms of that unit squared (say, inches^2). To express variance in the same units as the original random variable, we take the square root of the variance, yielding the standard deviation.

Standard deviation

The standard deviation of a RV \(X\) is defined as \(\text{SD}(X) = \sqrt{\text{Var}(X)}.\)

4.6.3. Alternate expression for variance#

Another way to express variance simplifies the computation by expanding the squared term:

This version of the formula shows that variance is the difference between the expected value of \( X^2 \) and the square of the expected value of \( X \).

4.6.4. Important properties of variance#

Shifting by a constant: Adding a constant \( c \) to \( X \) does not change its variance: \(\text{Var}(X + c) = \text{Var}(X).\)

Scaling by a constant: Multiplying \( X \) by a constant \( c \) scales the variance by \( c^2 \): \(\text{Var}(cX) = c^2 \text{Var}(X).\)

Independence: If \( X \) and \( Y \) are independent, the variance of their sum is the sum of their variances: \(\text{Var}(X + Y) = \text{Var}(X) + \text{Var}(Y).\)

Example: Variance of a binomial random variable

This is Example 4.6.5 from [BH19].

Recall that the if \( X \sim \text{Bin}(n, p) \), we can express \( X \) as the sum of \( n \) independent Bernoulli variables \( I_1, I_2, \dots, I_n \sim \text{Bern}(p) \): \(X = I_1 + I_2 + \cdots + I_n.\) For each \( I_j \), the expected value is \( \mathbb{E}[I_j] = p \), and since \( I_j^2 = I_j \), we have that \(\mathbb{E}[I_j^2] = \mathbb{E}[I_j] = p.\) The variance of each \( I_j \) is then \(\text{Var}(I_j) = \mathbb{E}[I_j^2] - \mathbb{E}[I_j]^2 = p - p^2 = p(1 - p).\) Since \( X \) is the sum of \( n \) independent indicators, the variance of \( X \) is: \(\text{Var}(X) = \text{Var}(I_1) + \text{Var}(I_2) + \cdots + \text{Var}(I_n) = np(1 - p).\)

4.7. Poisson#

Suppose a rideshare company wants to model the hourly distribution of ride requests it receives in Palo Alto. Let’s denote the random variable \( X \) as the number of requests per hour, and we aim to determine the probability \( \mathbb{P}[X = k] \), representing the likelihood of receiving \( k \) requests in any given hour.

Suppose that using historical data, the company estimates the average number of requests per hour as \( \mathbb{E}[X] = \lambda \). A natural question arises: could we model \( X \) using a Binomial distribution?

In a Binomial distribution, \( X \sim \text{Bin}(n, p) \) has expected value \( \mathbb{E}[X] = np \), and the probability of observing exactly \( k \) events is given by

If we approximate \( X \) as the sum of ride requests over each minute of the hour, we can think of it as the sum of 60 independent indicators:

where \( I_j = 1 \) if a request is made in the \( j \)-th minute and \( 0 \) otherwise. With this setup, we could choose \( n = 60 \) and rearrange \( \lambda = np \) to get that \( p = \frac{\lambda}{60} \). Under this model, we might approximate the probability of exactly \( k \) requests as:

However, this approach has a limitation: there could be multiple requests within a single minute. To refine the model, we might consider splitting each hour into 3,600 seconds instead, approximating \( X \) as:

where \( I_j = 1 \) if a request occurs during the \( j \)-th second. In this case, we set \( n = 3600 \) and adjust \( p \) such that \( \lambda = np \), giving \( p = \frac{\lambda}{3600} \). This allows us to model the probability of \( k \) requests as:

Even with seconds as intervals, we still face the issue that more than one request could occur per second. If we continue splitting the intervals into increasingly smaller units, in the limit, we would get that

In this case, we say that \(X\) has the Poisson distribution, written as \(X \sim \text{Pois}(\lambda)\). It’s not hard to show that \(\mathbb{E}[X] = \lambda\) (see the textbook).

This example motivates the Poisson paradigm/approximation, a useful approach for modeling the occurrence of rare events over many trials.

Poisson paradigm/approximation

Imagine we have \( n \) trials, each associated with a random indicator variable \( I_1, \dots, I_n \), where \( I_j = 1 \) if the \( j \)-th trial is a success and \( 0 \) otherwise. Here, the probability of success for each trial, \( \mathbb{P}[I_j = 1] = p_j \), is small, while the total number of trials \( n \) is large. Importantly, the trials don’t need to be independent of one another.

Under these conditions, the total number of successes, represented by \( I_1 + \cdots + I_n \), can be approximated by a Poisson distribution with parameter \( \lambda = \sum_{j=1}^n p_j \).

Here are some examples of the Poisson paradigm:

Customer arrivals at Starbucks: Suppose we count the number of customers who enter a Starbucks on a given day. Here, each trial could represent a specific minute, and a success occurs when a customer enters during that minute.

Emails received in an hour: Suppose we want to count the number of emails received in an hour. Each minute of the hour represents a trial, with a success occurring when a new email arrives during that minute.

In each of these examples, since there are many trials, each with a low probability of success, the total number of successes can be well-approximated by a Poisson distribution.

Example: Birthday triplets

Suppose we’re in a room with \( n \) people, and we want to find an approximate probability that three people share the same birthday. The Poisson approximation is a suitable tool here for the following reasons:

Setting up trials: Each trial involves checking a specific triplet of individuals \( (i, j, k) \) to see if they share the same birthday. With \( n \) people, the number of possible triplets is \( {n \choose 3} \), which is quite large as \( n \) grows.

Low probability of success: The probability that any specific triplet \( (i, j, k) \) shares the same birthday is very low. We define the indicator variable \( I_{i, j, k} \) such that \( I_{i, j, k} = 1 \) if individuals \( i \), \( j \), and \( k \) share the same birthday and \( I_{i, j, k} = 0 \) otherwise. Calculating this probability:

Define \( X = \sum I_{i, j, k} \), which counts the number of triplets with matching birthdays. According to the Poisson approximation, \( X \) can be approximated by a Poisson random variable with parameter \( \lambda = {n \choose 3} \cdot \frac{1}{365^2} \).

Now, the probability that at least one triplet of individuals shares the same birthday is given by:

For example, if \( n = 100 \), \( 1 - e^{-\lambda} = 0.7029 \), which remarkably matches the actual probability of 0.7029. Thus, the Poisson approximation accurately estimates the probability that three individuals share the same birthday.